written by DOUGLAS GREENWOOD

photography AVERY NORMAN

In the attic of a Dublin post-production house, typically frequented by movie folks, the artist Ronan Day-Lewis has temporarily set up shop. It’s early August, and two deadlines are looming. The 27-year-old is splitting his time between this spot, a makeshift art studio, and a grading studio across town, working late into the night. In just over six weeks from when we meet, he’ll present Anemoia, a new collection of his paintings at Los Angeles’ Megan Mulrooney Gallery. A few weeks later, his feature-length directorial debut, Anemone, will premiere at the New York Film Festival.

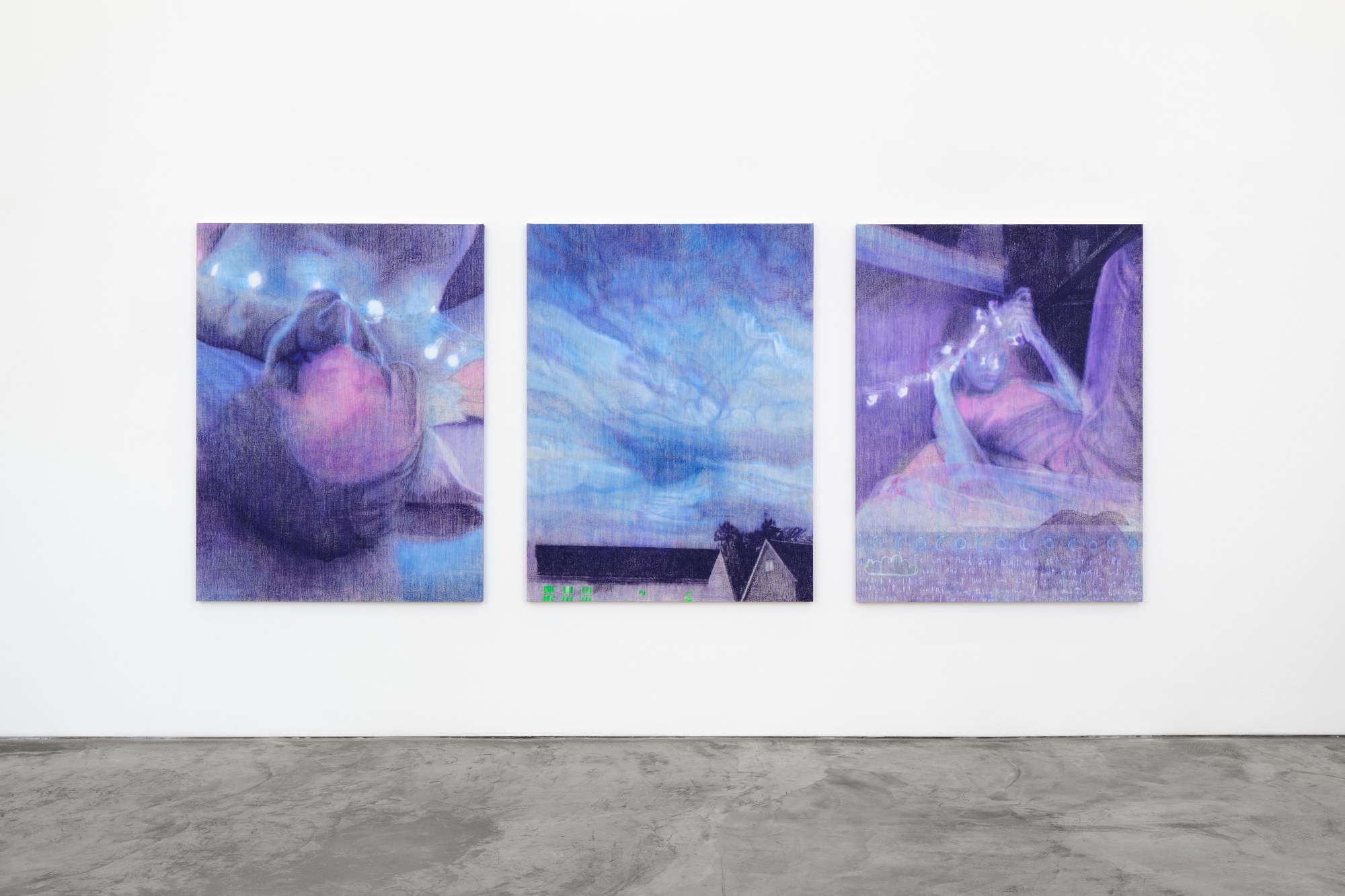

“I don’t know how I thought I would be able to do both at the same time,” he says, jovial but exhausted. Oil pastels are piled on a table, the acidic blues, greens, and violets already worn down. Six works hang on the walls with tape. “This is nice. It’s kind of the opposite to filmmaking—so solitary and reflective.” He laughs: “But yeah, my brain is like a pancake.”

Up until recently, he was editing the film in this building, two floors down. When the team wrapped, he’d come upstairs and paint until 11 p.m., sometimes later. Weekends were the same: headphones in, shoegaze on repeat (one Anemoia figure is based on the girl from Drop Nineteens’ Delaware cover). “I always veer toward chaos,” he says. That art-fueled delirium may have seeped into the work.

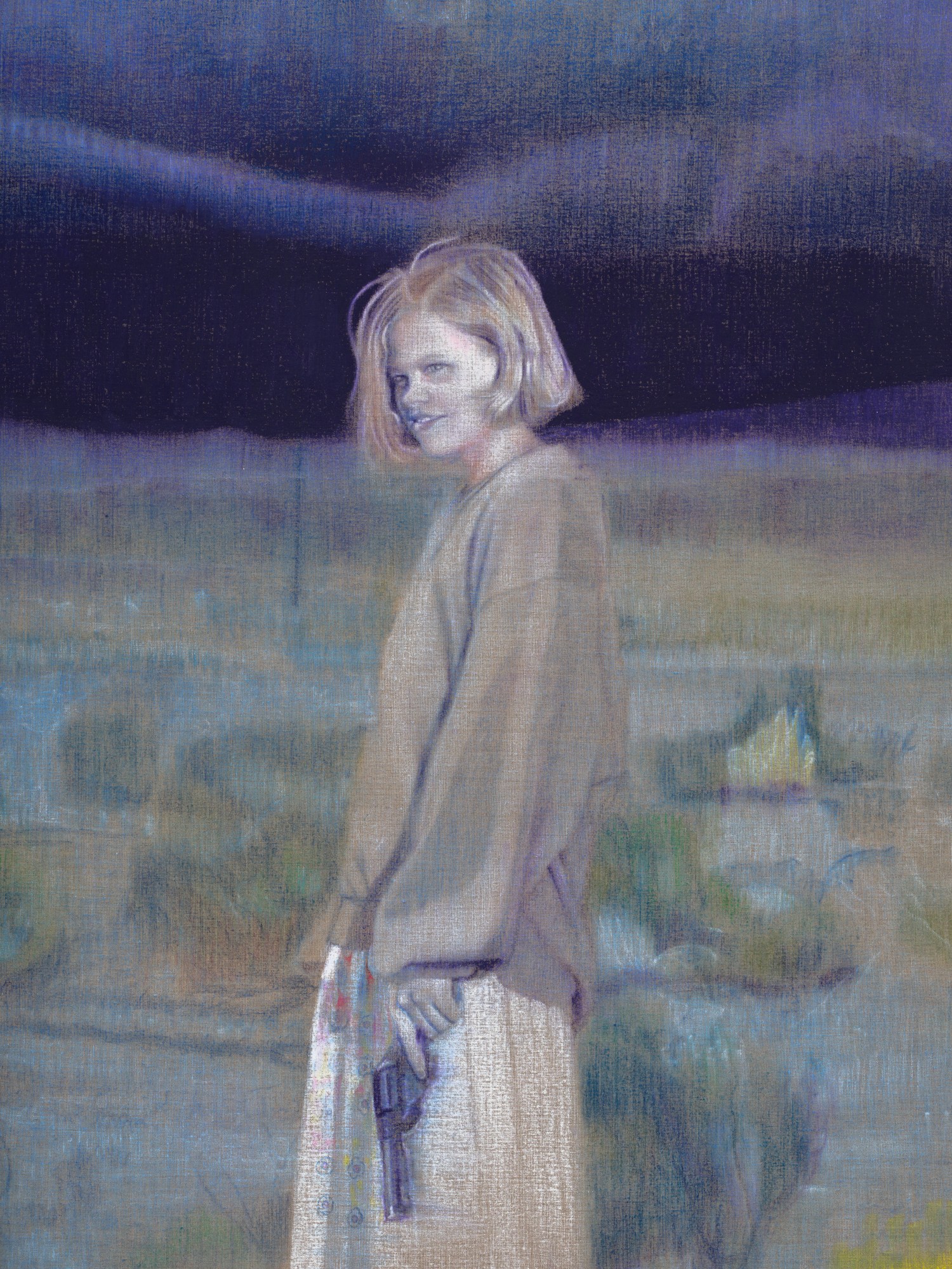

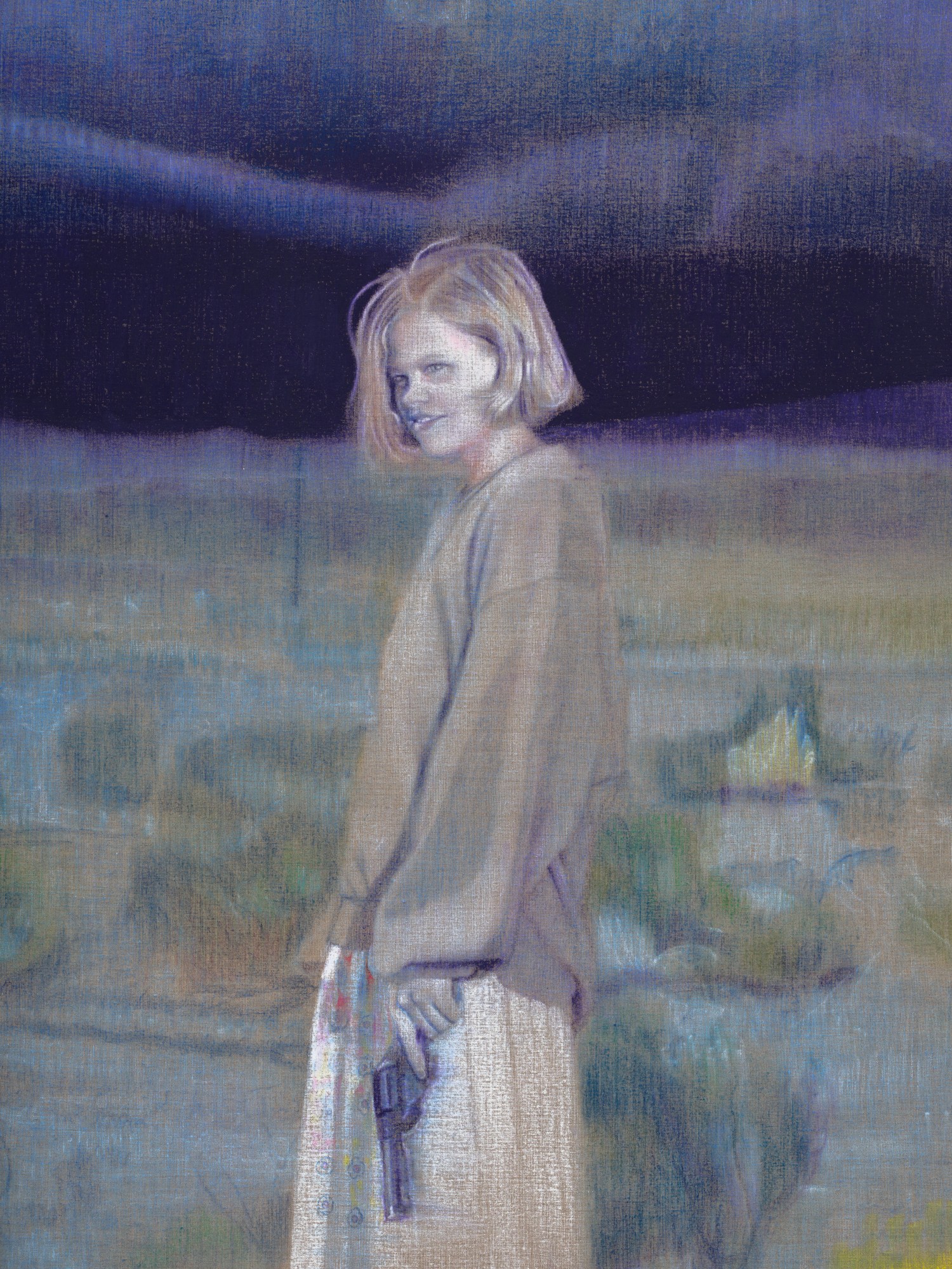

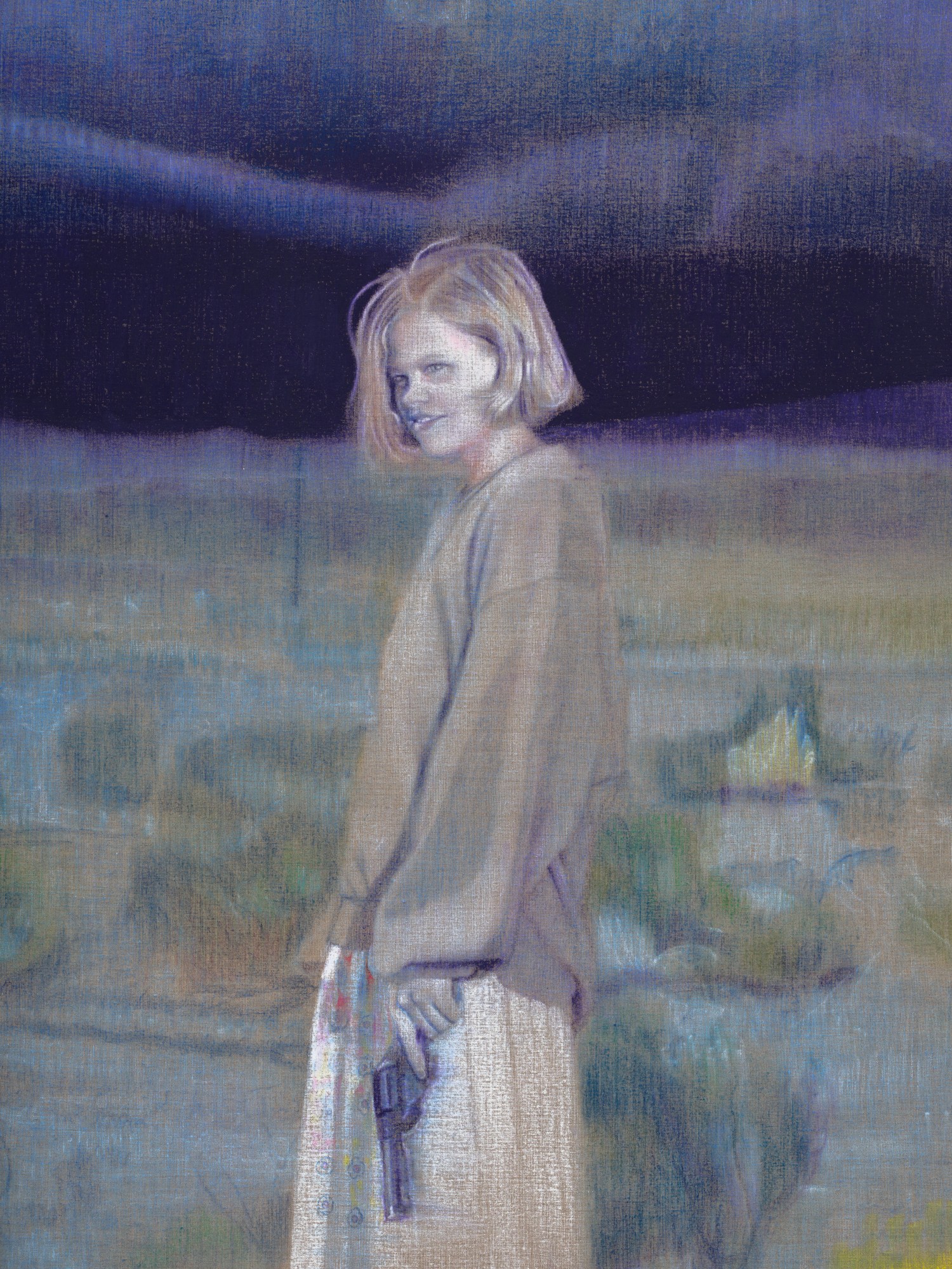

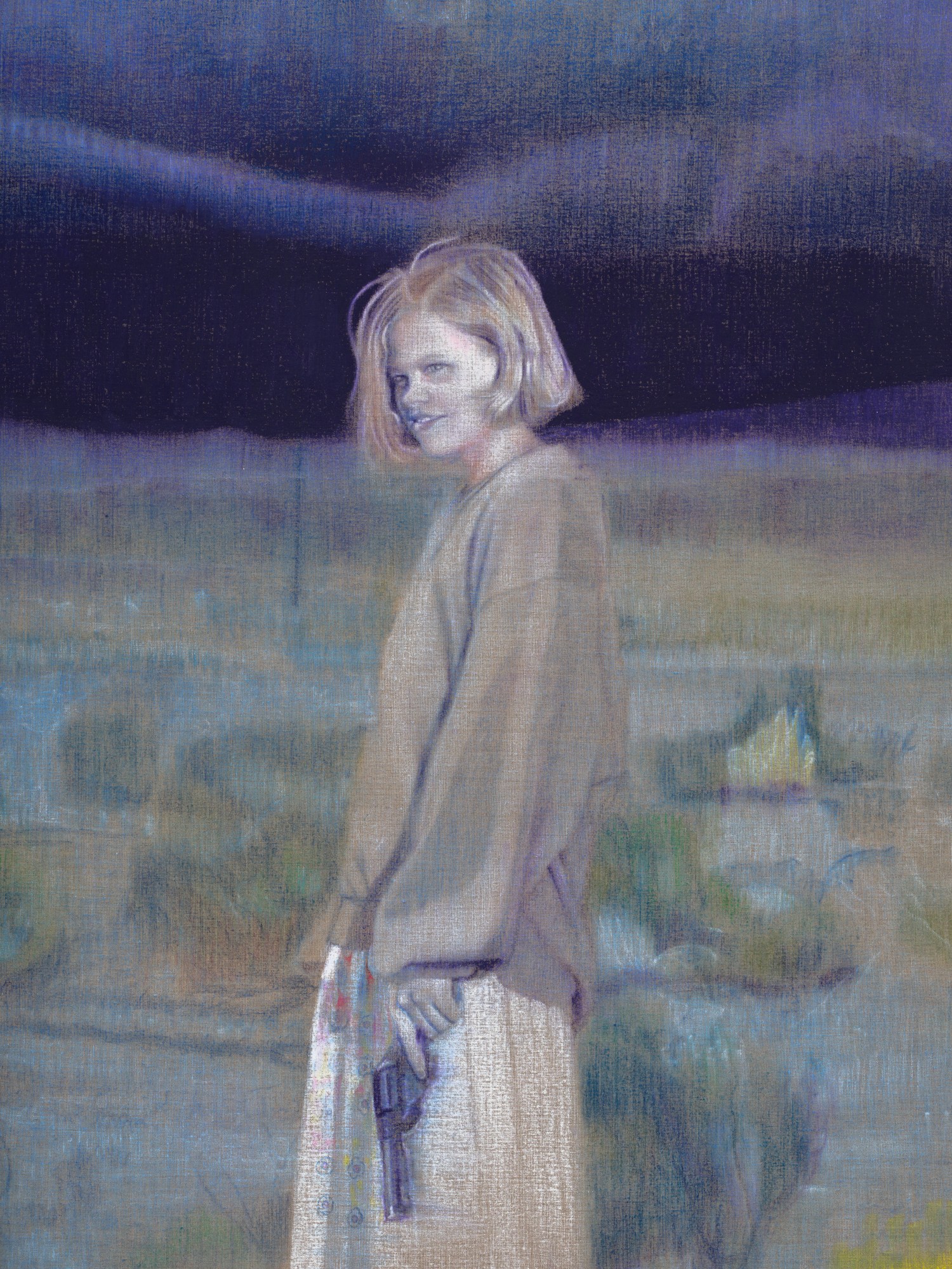

Anemoia—a term for nostalgia for a time and place you’ve never known—fits the oil pastel works on display at Megan Mulrooney. Some are almost photoreal, if not for their violent color. They feel reminiscent of a recent past. Like gazing through the window of the video store you frequented in your childhood, decades after it last opened its doors.

It’s a continuation of a body of work he started over a year ago, but its inspirations stretch back to the turn of the millennium. “[Each work] is based mostly on Flickr images from the early 2000s,” Day-Lewis says. Late one night, he was on a video call with his friend Wyatt, and they were crawling through the same Instagram account: @tvwishes. The account specializes in seemingly unremarkable snapshots by amateur photographers. “The images had this uncanny quality, where they weren’t quite contemporary, but they weren’t vintage feeling either,” he says. They were digitally dated between 2003 and 2007, and felt reminiscent, as the title suggests, of a world Day-Lewis hadn’t experienced—like a run-of-the-mill Midwestern high school. From here, he dove into Flickr “wormhole,” and found more of these images on his own. “I ended up finding this tapestry of images that called to me, that started to blur together in my mind,” he says. “I was no longer looking at this person’s life from 2004 and this person’s life from 2005. It congealed into a soup-like experience.”

That’s how the images manifest: a peculiar splicing of parts of different photos, placing figures in landscapes they’ve never seen. The works vary in scope. One captures endless, rumbling skies over house rooftops, another a vast, barren desert with a young girl brandishing a gun in the foreground. There are helium balloons on office ceilings and women in hotel room beds, captured off guard. They’re disconcerting, but looking at them also feels a little like being held, as if they’re glimpses from our dreams.

“I’m creating these altars to strangers’ memories, [and] finding this kinship with them in a way that’s actually completely fabricated,” Day-Lewis says. “The longer I spend with certain images, the more I feel like I almost know the people in them.”

That fascination with the way time plays with memory is one of the things that binds Anemoia with Anemone. But while creating the exhibition has been a mostly solitary task (seeking advice opens sinkholes for him), the film involves millions of moving parts. He’s made music videos and short films in the past, but never anything on this scale.

That said, it’s still a contained and isolating character study, much like the films his father—the Oscar-winning actor Daniel Day-Lewis—was drawn to before he stepped back from acting in 2017. Daniel returns here, both as the lead actor and the film’s co-writer.

Beyond a vague plotline (an exploration of “the bonds between fathers, sons, and brothers”) and the fact that Focus Features and Plan B, who helped produce Moonlight and Adolescence, were behind it, very few people knew anything at all about Anemone. That mystery made shooting and editing easier for Day-Lewis. “It’s allowed me to be in slight denial about how many people are going to see it,” he says.

“For years before we started writing, I’d had this idea that I wanted to write something about brothers,” Day-Lewis reminisces. Back in the early days of the pandemic, he thought it might be a coming-of-age story, until he realized his dad had a similar thing in mind. So they joined forces.

“We had a rough idea of where we were going,” Day-Lewis says of the script, “but it was kind of like walking into the dark with a flashlight. Neither of us were even sure exactly if or when it would materialise into a full feature.” Together, passing it back-and-forth over the course of four years, they crafted the script into what it is now: a film about an self-exiled former soldier named Ray (Day-Lewis), and what brings him back into contact with his brother (Sean Bean) after a long time apart. Though Ray has some towering monologues, much of the film lives in the silences they share. It’s a brutal and fascinating project for a father and son to have created together, with flecks of the younger half’s eye for abstraction.

Day-Lewis’s attunement to art started young. As a child, he loved drawing and was fascinated by the paintings his mother had created in her 20s: images of a “childlike creature” with a triangular head sitting at a table, which hung from his grandparents’ walls. “It was inscrutable to me,” he says, “but it had this kind of strange power.” At 5, he saw Ken Loach’s Kes, which revealed to him the mighty potential of cinematic language: “I feel like I’m always chasing that kind of spirit,” he says.

Though his family was mostly based in rural Ireland, his parents’ work sometimes took him elsewhere. He visited Prince Edward Island during the shoot for The Ballad of Jack and Rose, and Marfa, Texas on the set of Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood. Even as a kid, Day-Lewis seems to have absorbed the filmmaker’s spirit, carrying those landscapes into his art.

When he was old enough, Day-Lewis moved to New York, studied art at Yale, and liked it. There he made his first short films and discovered the caustic color palette that would define his work (“My eyes just slowly adjusted over time, to the point where [that palette] almost became neutral”). He met his best friends, his girlfriend the painter Lenna Christakis, and took part in an experimental theater group. “I have never done any other kind of performance,” he says. “Twice a week, we’d split into groups and devise pieces, then perform them in different spaces around campus. At the end of each semester, we’d synthesize the work in a kind of chaotic scramble into a show.” Everyone did a bit of everything—including acting. “It was exhilarating, because it was low stakes, basically for our friends,” he says of his brief thespian experience. Is acting in his past? “I think it probably is, yeah…” he says, laughing. Then clarifies, for the record: “Definitely!”

Thankfully, he has more talent in other places. After the film premieres, Day-Lewis has to start work on another painting show, set to launch in early 2026. “And then I have a film I really want to make,” he says—one that’s been on his mind since before Anemone.

In the studio, a piece of fabric on the wall bears a hand-written message I can’t read from where I’m sitting. Day-Lewis calls it “the seed of something,” and says that if he were back in his Brooklyn studio, he’d have written it straight onto the walls. Maybe it’s for the show—he’s not sure yet—but I ask him to read it to me:

“The mystery. You looked like you knew something, something, something, some…”

He laughs after reciting it, as if it’s minor or throwaway. But it carries the kind of atmosphere that percolates through everything he’s making right now—whether a surreal painting of an imagined place or person, or a film about the things the ones we love leave unsaid.

Anemoia runs at Megan Mulrooney Gallery, Los Angeles until November 1. Anemone will have a limited release in North American theaters on October 3, before being released wide on October 10. It will open in UK theaters on November 7.